About

Rooted in a Story of Trauma Recovery

Founded by psychotherapist and author Benjamin Fry in 2012, Khiron Clinics was created to offer other people the groundbreaking trauma therapies that once saved his life. Since then, Khiron Clinics has become globally recognised as a leading centre in the treatment of trauma.

“It's a unique place that is really able to offer people something that will put them on the path towards healing and isn't available anywhere else.”

Deb Dana

A Global Leader in Trauma Recovery

Delivering Specialised Trauma Care in Both Residential and Outpatient Settings, We Guide Individuals from Crisis to Cure

Our clinicians are informed, trained and supervised by some of the world's top trauma experts including Dr Bessel van der Kolk, Dr Janina Fisher, Dr Stephen Porges, Dr Dick Schwartz, Deb Dana, Licia Sky and Linda Thai.

We are the world's first Polyvagal Informed certified residential clinic, ensuring that every team member, from our gardener to the board, is well-versed in trauma.

We deliver innovative neurobiological therapies which are at the cutting edge of trauma treatment in residential and outpatient environments which are specifically designed to treat trauma.

We listen to what works instead of only following traditional therapies, which is why we also offer activities such as yoga, equine therapy, tai-chi, breathwork, cold water therapy, ecotherapy and more.

To make our life-saving treatment globally accessible, Khiron Clinics organises and pays for transport for all international clients to the residential clinics and home again, making sure they are supported every step of the way.

We have multiple levels of care, creating a pathway to ensure that there are suitable options all the way from an alternative to hospital care to weekly outpatient therapy sessions, either online or in-person.

From Breakdown to Breakthrough

How Uncovering a New Understanding of Trauma Allowed Our Founder to Rebuild His Life and Wellbeing, Igniting a Newfound Purpose to Provide Others With the Same Chance of Recovery

Note From Our Founder:

…It was in 2009 that I finally had a breakdown, after what I later realised was an entire life spent running from what I call ‘the invisible lion’. Because of various incidents of childhood trauma I had experienced such as the death of my mother as a baby, I had a nervous system which was constantly reacting as if I was in great danger, as if I was being chased by a lion.

Ultimately, everything caught up with me, and after many failed attempts at recovery with a variety of treatments, including stays in famous residential treatment settings, I had the good fortune to meet a therapist who totally changed the narrative of what I was experiencing, and therefore paved the way for me to find true, lasting healing.

She explained how my reactions, thoughts and feelings were actually an entirely normal response to the perceived threat I was experiencing due to unresolved trauma in my life. This transformed everything for me, and the subsequent nervous system based treatment based on this understanding saved my life.

As my own life recovered, I knew very simply that I not only had to let others know about this groundbreaking approach to trauma treatment, but create a safe space where it could be experienced too. Something that didn’t exist then, and which I have yet to find to this day.

Today, Khiron Clinics stands as a beacon of hope for those seeking lasting recovery from mental health challenges who, like me, once felt hopeless.

Download the Brochure

Discover Our Innovative Trauma Recovery Pathway

Meet the Team

“Unlike previous experiences, the therapists at Khiron honestly saved my life. They were there to hold my hand and help me to help myself. All of the members of the therapeutic team have a genuine understanding of trauma and how to treat it.” - Andrea

The clinical team at Khiron Clinics comprises world-class mental health and trauma treatment specialists. They have been informed, trained and supervised by some of the world’s top trauma experts, including Dr Bessel Van Der Kolk, Dr Janina Fisher, Dr Stephen Porges, Deb Dana, Dr Dick Schwartz, Licia Sky, Linda Thai and others.

Aside from the incredible therapists, we ensure that every member of our team from the board to the gardener speaks the ‘language of trauma’, creating a safe and supportive environment at all our clinics.

The Leadership Team

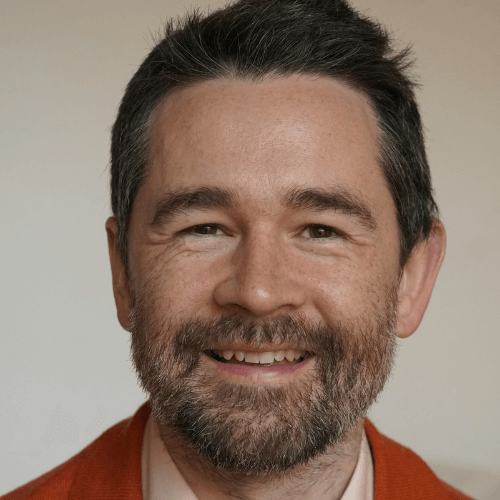

Benjamin Fry

Founder and Chair

Benjamin is a psychotherapist, accredited by the BACP, who contributes to the media in the UK and is politically active in lobbying for better access to better treatment for all sections of society, working with the Centre for Social Justice and through Khiron House’s social enterprise Get Stable. He set up Khiron House after experiencing serious mental illness in 2009 and not receiving effective treatment for it in the UK. He is the Founder of Khiron Clinics and the non-executive Chair of the Board of Directors. He is the Treasurer of Bessel van der Kolk’s Trauma Research Foundation.

Romana Akram

Managing Director

Romana Akram is the Managing Director of Khiron Clinics. She is based at the residential clinic. Prior to joining the Khiron Clinics team, she worked in a residential setting, caring for the elderly, and then she joined a publishing firm as a business systems coordinator. Romana has a special interest in implementing new procedures to maximise efficiency. Romana has an MBA and is a member of the Board of Directors.

Tracey-Lee Austin

Service Supervisor

Tracey has a Masters degree and a Doctoral degree in Clinical Psychology and is HCPC registered. She has a diploma in Schema Therapy and has completed Sensorimotor Training Level 1, Brainspotting Levels 1 and 2, Bodynamic Foundation Level, and BWRT level 1. She is a qualified Somatic Experiencing Practitioner and has also complted training in wrking with trauma and the breath. Her background is in working with Complex PTSD, Dissociative Disorders, Mood and Anxiety disorders, Attachment disorders, Personality disorders, and Psychosis, drawing from a variety of approaches including Polyvagal Theory, Schema Therapy, IFS, Sensorimotor and Somatic therapies, Mindfulness, and Structural Dissociation. Tracey is the Service Supervisor at Khiron Clinics.

The Operations Team

Romana Akram

Managing Director

Romana Akram is the Managing Director of Khiron Clinics. She is based at the residential clinic. Prior to joining the Khiron Clinics team, she worked in a residential setting, caring for the elderly, and then she joined a publishing firm as a business systems coordinator. Romana has a special interest in implementing new procedures to maximise efficiency. Romana has an MBA and is a member of the Board of Directors.

Angela Bent

Intake Director

Angela Bent is the Intake Manager at Khiron Clinics. Angela has worked for Khiron Clinics since 2013, beginning as a support worker and then moving on to become House Manager at the residential clinic. Angela now works as the Intake Manager managing initial enquiries, referring clients on for initial consultations and admission. Angela is a qualified paralegal, having worked in the legal field for over twenty years.

Emilia Haanpaa

Clinical Assistant - Outpatients

Emilia is the Clinical Assistant for the outpatient services, including the Day Clinic, Outpatients, and Child & Adolescents. Emilia joined Khiron Clinics in 2023 after completing her BSc (Hons) in Psychology. She is responsible for managing all bookings for the outpatient services, as well as running and maintaining the Day Clinic daily. Her role includes doing admissions, supporting the therapists, serving as a contact point for all clients, and performing administrative tasks. Emilia works closely with the Clinical Director of the outpatient services and assists her with tasks such as initial consultations. Emilia has also completed Level 2 in Counselling Skills and an Evidence-Based Therapies course.

Grace Poffley-Ifill

Operations & Registered Manager

Samantha Gould

Clinical Assistant - Residential

Samantha Gould is the Clinical Assistant for the Residential Clinic. She brings a wealth of experience from a long career in communications, alongside a decade of clinical responsibility and team management within a Primary Care setting. This combination provides her with strong practical insight and a well-rounded understanding of client care and organisational needs.

In her role at Khiron, Samantha oversees admissions, supports therapists, acts as a key point of contact for clients, and manages essential administrative and operational tasks that help ensure the smooth running of the clinic.

Nicola Bowler

House Keeping Executive

Nicky brings over 15 years of experience across the health, hygiene, and food industries. She has previously worked within the NHS, facilities management companies, and food manufacturing, gaining broad operational knowledge and extensive practical expertise.

With significant involvement in health and safety throughout her career, Nicky brings a strong understanding of regulatory standards, risk awareness, and best practices within workplace environments. She is committed to maintaining clean, safe, and well-organised spaces that support the wellbeing of both clients and staff.

Nicky also holds a Level 3 Certificate in Food Safety and Hygiene, further demonstrating her commitment to high-quality standards, compliance, and operational excellence.

Residential Clinic Team

Amber Knights

Clinical Director - Residential

Amber is a psychotherapist at Khiron residential clinics and our outpatient service, She specialises in trauma, suicide prevention and sexual abuse. She also works with addiction, gender issues and depression. Amber has a Masters Degree in Gestalt Psychotherapy, a modality that is person-centred and has a strong focus on the therapist-client relationship, awareness and the body. Amber uses a combination of her skills in Gestalt therapy, the polyvagal theory, and her own creativity to facilitate supporting individuals in their journey towards healing. Whilst living in Malta, she was a casual lecturer in victimology at the University of Malta and managed a therapeutic service for victims of crimes. She is a member of GPTI. Amber has a great love for animals and began her career working with them alongside people. Whilst in the USA she worked at the Human-Dolphin Institute providing dolphin assisted therapy to vulnerable people.

Lucy Allen

Lead Therapist

Tracy Ellis

Therapist

Sarah Paton Briggs

Psychotherapist

Sarah has practised as a counsellor and psychotherapist for over 20 years. She has trained in the two evidence-based trauma treatment protocols which are recommended by NICE: EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization Reprocessing) and T- CBT (Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioural Therapy).

She is also trained in other approaches to treating trauma because different methods suit different client needs. These include BEPP (Brief Eclectic Psychotherapy for Psych traumatology). Her hypnotherapy and NLP qualifications equip her with imagery-based approaches to treating trauma, including IRRT (Imagery Rescripting Reprocessing Therapy) and Matrix Reimprinting. Sarah is recognised by ITTI (International Trauma Training Institute, formerly IATP) as a Certified Clinical Trauma Professional at the higher level (CCTP Level 2) for working with Complex Trauma (C-PTSD). Sarah supports Khiron residents with equine therapy with her horses.

Rachel James

Yoga Teacher

Rachel is the Yoga teacher at Khiron Clinics. Rachel has been practicing Yoga for over 30 years and teaching since 2006. Rachel trained to become a Hatha Yoga teacher with the British Wheel of Yoga, graduating in 2009. Rachel has extensive training in Anatomy and Physiology, with a special interest in the Nervous System, the Brain and the Vagus Nerve. She follows a trauma-informed approach to working with the body and is highly skilled in adapting her yoga classes to clients with mobility issues. She has worked in many fitness centres, corporate businesses, educational settings, community classes and private practice. She holds regular workshops based on Longevity, Posture and the Chakras and has held yearly Yoga retreats in Tuscany since 2016. She held the role as Oxfordshire County Representative for the British Wheel of Yoga for 3 years (2013-16).

Sidney Hays

Psychotherapist

Sidney is a psychotherapist at Khiron residential clinics. She obtained a BA in Psychology and a Masters degree in Social Work at the University of Cincinnati. She has worked in many settings including community mental health, jails, psychiatric hospital, and outpatient psychotherapy in the US before relocating to the UK to join Khiron. Her primary specialties have been working with complex, developmental and relational trauma, chronic illness, eating disorders, intimacy and relationships, as well as with high achieving individuals struggling with self image and relationships. Sidney is a certified Developmental and Relational Trauma Therapist (DARTT) and facilitator through the Healing Our Core Issues Institute. She has experience and training in Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), Radically Open Dialectical Behavior Therapy (RODBT), somatic embodiment and self regulation, sex therapy, Trust Based Relational Intervention (TBRI), polyvagal theory, and EMDR. Sidney aims to create an environment of safety and curiosity that allows space for the fullness of each individual to be seen, heard, and valued in a way that opens possibilities for lasting shifts and change.

James Booth

Fitness Instructor

James is a dedicated fitness professional with over five years of experience in the health and wellness industry. He specialises in both group training and one-to-one coaching, working with clients of all backgrounds, abilities, and goals.

His approach goes beyond just workouts — James is passionate about helping people improve their overall quality of life by building sustainable habits, developing a better understanding of nutrition, and fostering a positive relationship with movement and health.

In 2017, his hard work and dedication led him to proudly represent Great Britain in a powerlifting competition — a testament to his commitment to personal excellence and high performance.

Whether someone is just starting their fitness journey or aiming to reach the next level, James provides the guidance, support, and motivation needed to succeed.

Dr. Lisa M. Kleyn

Psychotherapist

Janine Hadley

Therapist

Janine began her professional journey with a BA (Hons) in Psychology before expanding into body-based therapeutic modalities. She works from a foundation of Somatic Experiencing and is also a Somatic Art Practitioner (Tamalpa) and an EMDR practitioner. In addition, she has completed short courses in parts work and Polyvagal Theory.

Janine views every therapeutic approach as a potential key or tool, recognising that no single method works for everyone. She makes it a priority to understand each client and their nervous system, seeing the individual in front of her — their struggles, strengths, pain, and joy — and tailoring her approach accordingly. She uses the modalities best suited to each unique person.

Her experience includes working with dissociation, PTSD, depression, attachment wounds, sexual abuse, and childhood abuse or neglect.

Mary Oakes

Therapist

Mary is a somatic experiencing practitioner (SEP) and an accredited member of EASE. She is a trauma therapist with training in Somatic Experiencing, foundation in psychodynamic counselling and psychotherapy, polyvagal theory, nutrition, cold water, neurodivergence and creative Expression.

Mary continues her professional development in trauma healing including Janina Fisher’s Tist (level 1) and Richard Swartz IFS (level 1). Developing her psychotherapeutic training doing an MSC in Transactional Analysis psychotherapy and a continuation of her neurodivergent education by becoming a neurodivergent practitioner.

Mary has worked with diverse client groups and has a special interest in working with neurodiverse individuals and those with complex mental health needs such as CPTSD, borderline personality disorder, dissociative identity disorder (DID), depression and anxiety.

Practising in a somatic, multi-functional and compassionate way, she is passionate about supporting, empowering and providing a personalised toolbox for her clients to takeaway to continue their own recovery. She is dedicated to helping her clients develop their own identity through supporting them to connect and listen to their bodies, through movement, and an understanding of their own nervous system, gut health and internal systems to support safety, regulation, processing and ultimately healing that lasts beyond Khiron.

Shreya Sinha

Psychotherapist

Day Clinic Team

Anja Frykegaard

Clinical Lead - Outpatients

Anja is a BACP accredited psychotherapist. She holds a BSc in Psychology, as well as a Master’s degree in Psychodynamic Psychotherapy. She is a certified Neurofeedback Practitioner and is currently on her last year of SE training, working towards becoming a Somatic Experiencing Practitioner (SEP).

Anja’s therapeutic approach is rooted in a deep understanding of the mind-body connection. She integrates a wide range of therapeutic modalities, including Reichian Body Psychotherapy, Deep Brain Reprocessing (DBR), Internal Family Systems (IFS), the Structural Dissociation Model, Attachment Theory, and Mindfulness Practices. Additionally, she holds certifications in Somatic Embodiment and Regulation Strategies, Bodylistening, Dance of Awareness, and Trauma-Informed Breathwork.

She specialises in developmental trauma, loss, abuse, neglect, self-harm, identity issues, relationship difficulties, PTSD, and C-PTSD. Her approach is both creative and collaborative, ensuring that everyone receives a personalised treatment plan tailored to their needs.

Anja is passionate about creating a safe and trusting environment, using the therapeutic relationship to facilitate support and connection where it has been lost or damaged. She firmly believes in the immense capacity within each person to heal and grow, and she is dedicated to guiding her clients in their healing towards greater self-awareness, resilience, and well-being.

Arielle Swann

Psychotherapist

Arielle is a registered Dance Movement Psychotherapist (ADMP) who has engaged in 6 years of training in psychotherapies including MA dance movement psychotherapy, Bachelor in Arts Psychotherapy and advanced diploma in Transpersonal Arts Psychotherapy.

Over the past 8 years, Arielle has worked with clients using a combination of therapeutic methods, including Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, Arts Psychotherapy, Dance Movement Psychotherapy, Somatic Experiencing, Polyvagal Informed Therapy, and Trauma-informed stabilisation techniques. Her clinical practice center’s on both a combination of talk therapy psychotherapy approaches and somatic work. She has currently engaging in research exploring body-based regulation approaches for working with adults experiencing trauma.

Arielle has worked in various clinical settings, including private rehabilitation center’s, the Blue Tree Private Psychiatry Centre, the Maggie Oliver Foundation, Barnet Integrative Clinical Services, Universities, Schools and private rehabilitation settings. Additionally, she offer’s consultancy services to corporate settings supporting individuals with performance, stress, anxiety, burnout, self-esteem, and career/purpose. Arielle has extensive experience working with clients dealing with trauma, PTSD, self-esteem, career/purpose issues, intimacy and relationship challenges, depression, anxiety, stress, and burnout.

Alice Pegram

Psychotherapist

Shreya Sinha

Psychotherapist

Janie Rymaszewska

Psychotherapist

Janie qualified in 1990 as a creative arts therapist (MCAT) at Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance. She has 25 years of experience as a therapist with children and young people with relational trauma and was clinical lead for seven years with children in therapeutic residential care. Her approach is supported by modern attachment theory, neuroscience, and trauma-sensitive interventions.

Janie is a proficient Story Stem Assessment Profiles (SSAP) assessor and trained at the Anna Freud Centre for Children & Families.

The storytelling technique explores the workings of a child’s mind to understand how they perceive grown-ups. The approach permits an assessment of a child’s expectations and perceptions of family roles and relationships without asking direct questions about family, which could cause conflict or anxiety.

In 2005, Janie was commissioned to set up specialist play provisions for a children’s hospital in Nairobi, Kenya. She was a course tutor for a Master’s programme in play therapy at Liverpool Hope University. In 2006, Janie published Reaching the Vulnerable Child. Therapy with Traumatized Children. (Jessica Kingsley) and has published articles in Young Minds.

Outpatient Clinic Team

Anja Frykegaard

Clinical Lead - Outpatients

Anja is a BACP accredited psychotherapist. She holds a BSc in Psychology, as well as a Master’s degree in Psychodynamic Psychotherapy. She is a certified Neurofeedback Practitioner and is currently on her last year of SE training, working towards becoming a Somatic Experiencing Practitioner (SEP).

Anja’s therapeutic approach is rooted in a deep understanding of the mind-body connection. She integrates a wide range of therapeutic modalities, including Reichian Body Psychotherapy, Deep Brain Reprocessing (DBR), Internal Family Systems (IFS), the Structural Dissociation Model, Attachment Theory, and Mindfulness Practices. Additionally, she holds certifications in Somatic Embodiment and Regulation Strategies, Bodylistening, Dance of Awareness, and Trauma-Informed Breathwork.

She specialises in developmental trauma, loss, abuse, neglect, self-harm, identity issues, relationship difficulties, PTSD, and C-PTSD. Her approach is both creative and collaborative, ensuring that everyone receives a personalised treatment plan tailored to their needs.

Anja is passionate about creating a safe and trusting environment, using the therapeutic relationship to facilitate support and connection where it has been lost or damaged. She firmly believes in the immense capacity within each person to heal and grow, and she is dedicated to guiding her clients in their healing towards greater self-awareness, resilience, and well-being.

Lorena Balbinot

Psychotherapist

Lorena is a psychotherapist at Khiron Residential Clinics and Khiron Outpatient service. She is a trauma therapist with an MA in Integrative Arts Psychotherapy, a diploma in Humanistic Body-Centred Counselling, and she is a qualified Bioenergetics teacher.

Her work is informed by Psychodynamic & Humanistic psychotherapy, Attachment Theory, Object Relations, Gestalt, Transactional Analysis, Integrative Arts, Janina Fisher’s Structural Dissociation model, and Reichian Character Analysis.

She continues her professional development in cutting-edge approaches for trauma healing, including Somatic Experiencing (Level 2), Sensorimotor Psychotherapy (Level 1), Relational Trauma Therapy (Level 2), and Integral Somatic Psychology.

Practising in a relational, compassionate, and present-oriented way, she is committed to empowering clients by helping them understand the role of the nervous system in their global experience and offering tools to help them take charge of their wellbeing.

Lorena has worked in inpatient and community mental health settings within the NHS, addiction and family services in charitable organizations, and her own private practice.

Her experience includes working with PTSD & CPTSD, addiction, co-dependence, narcissistic abuse, stress, anxiety, depression, anger management, OCD, bereavement, grief, the LGBTQ+ community, low self-esteem, shame, racial trauma, attachment issues and disorders, dissociation, BPD, psychosis, self-harm and suicidality.

Sasha Watson

Psychotherapist

Rachel James

Yoga Teacher

Rachel is the Yoga teacher at Khiron Clinics. Rachel has been practicing Yoga for over 30 years and teaching since 2006. Rachel trained to become a Hatha Yoga teacher with the British Wheel of Yoga, graduating in 2009. Rachel has extensive training in Anatomy and Physiology, with a special interest in the Nervous System, the Brain and the Vagus Nerve. She follows a trauma-informed approach to working with the body and is highly skilled in adapting her yoga classes to clients with mobility issues. She has worked in many fitness centres, corporate businesses, educational settings, community classes and private practice. She holds regular workshops based on Longevity, Posture and the Chakras and has held yearly Yoga retreats in Tuscany since 2016. She held the role as Oxfordshire County Representative for the British Wheel of Yoga for 3 years (2013-16).

Shreya Sinha

Psychotherapist

Alice Pegram

Psychotherapist

Arielle Swann

Psychotherapist

Arielle is a registered Dance Movement Psychotherapist (ADMP) who has engaged in 6 years of training in psychotherapies including MA dance movement psychotherapy, Bachelor in Arts Psychotherapy and advanced diploma in Transpersonal Arts Psychotherapy.

Over the past 8 years, Arielle has worked with clients using a combination of therapeutic methods, including Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, Arts Psychotherapy, Dance Movement Psychotherapy, Somatic Experiencing, Polyvagal Informed Therapy, and Trauma-informed stabilisation techniques. Her clinical practice center’s on both a combination of talk therapy psychotherapy approaches and somatic work. She has currently engaging in research exploring body-based regulation approaches for working with adults experiencing trauma.

Arielle has worked in various clinical settings, including private rehabilitation center’s, the Blue Tree Private Psychiatry Centre, the Maggie Oliver Foundation, Barnet Integrative Clinical Services, Universities, Schools and private rehabilitation settings. Additionally, she offer’s consultancy services to corporate settings supporting individuals with performance, stress, anxiety, burnout, self-esteem, and career/purpose. Arielle has extensive experience working with clients dealing with trauma, PTSD, self-esteem, career/purpose issues, intimacy and relationship challenges, depression, anxiety, stress, and burnout.

Mark Kelly

Therapist

Mark is an experienced Somatic Experiencing Practitioner and Somatic Coach working in private practice since 2020. He worked for 2.5 years at Khiron Clinics in 2022 running groups and offering 1-1 therapy sessions. He has a spacious and intuitive capacity to support clients through traumatic experiences. He has been touched and inspired by his clients capacity to live life more fully as they courageously face their trauma with respect and gentleness.

Mark danced professionally for 30 years beginning at 12 years old studying classical ballet and other disciplines. These many years of movement practice offers a gift of presence to his work with clients. Being able to slowly and respectfully invite clients in to a new relationship with their body can be like a sense of coming home. This also includes making more space for that which was too much in the past. Slowly, moving towards challenge and coming back to embodied resources.

Mark is a life learner of many healing modalities , meditation , visionary craniosacral work , reiki and a wealth of somatic practice. This brings much joy to his life. His ongoing personal therapy and healing is an offering in the work with clients.

Mark has clinical experience working with sexual trauma, sexuality, developmental trauma, boundary breaches, PTSD, C- PTSD, grief and depression. Through his warm hearted way of being he creates a space for his clients unfolding and healing.

Tracy Ellis

Therapist

Next Steps

We Are Here to Help You Find the Path to Effective, Long Lasting Recovery.

Talk to Us

Get in touch with us and share your story if you feel comfortable with someone who will listen. Our team are always here to help.

Book an Initial Consultation

Meet with a senior member of our clinical team and get insights into the root causes of your issues, plus a written summary and treatment recommendation.

Download Our Brochure

Discover our innovative trauma recovery pathway. Find out more about how we treat, what we treat, our clinics, pricing and more.

Professional Memberships and Associations

We Work With Members of Respected Organisations to Deliver Our Services