The nervous system is a complex network of nerves, neurons, cells, and signals extending throughout the body. While also managing essential bodily functions, it influences mental health, general well-being, and trauma responses.

Trauma impacts the nervous system in multiple ways, contributing to many physical and mental symptoms and impacting its ability to regulate itself. To understand how trauma can affect and dysregulate the nervous system, it is vital to first understand the parts of the nervous system and how it works.

This two-part series will look at the various components of the nervous system and what they control before exploring how this influences trauma, healing, and mental health.

The Central and Peripheral Nervous Systems

The nervous system is not just one structure. It consists of many systems that govern different bodily functions. The central nervous system (CNS) is the main hub of the nervous system. It contains the brain and spinal cord and is insulated from the rest of the body. It analyses and calculates information, responding to sensory input and controlling muscle movement and motor function.[1]

The CNS acts as a central processing centre, receiving sensory input from every part of the body and interpreting the information via the brain. However, this would be impossible without the peripheral nervous system (PNS).

The PNS comprises everything connected to the CNS. It includes connections to all the limbs, organs, and spinal nerves, which carry information back to the CNS for processing. For example, if someone touches a sharp thorn on a rose bush, the PNS sends the signal to the CNS, which processes the painful sensation and causes the person to jerk their hand away.

The primary functions of the PNS include:

- Controlling autonomic body functions

- Motor movements

- Digestion

The PNS splits into two parts, each of which plays a critical role in the body’s function.

The Somatic Nervous System

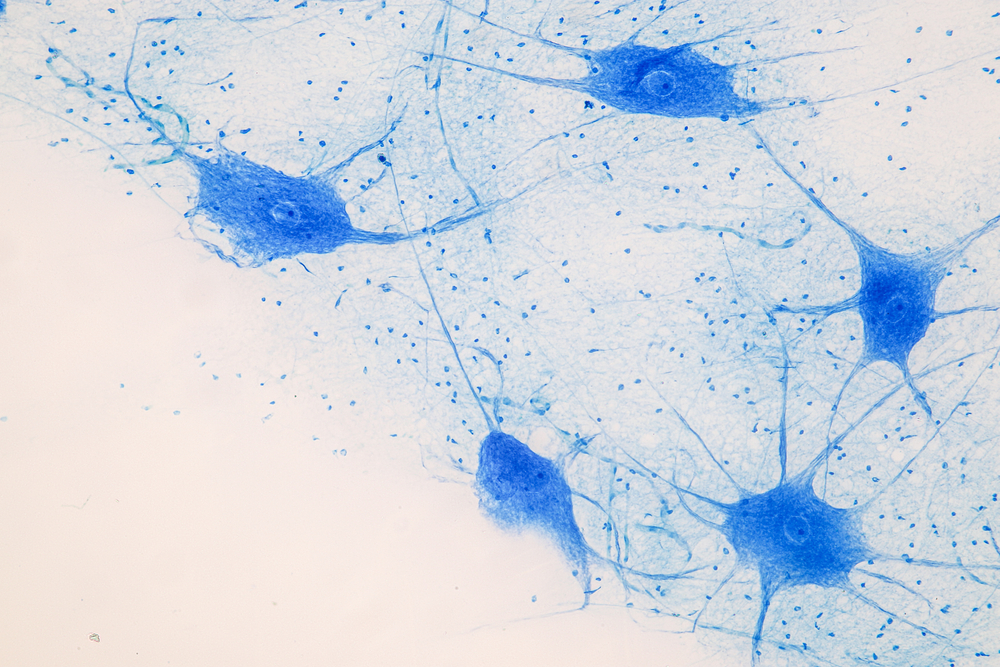

The somatic nervous system is a subsection of the PNS that carries motor and sensory information to and from the CNS. It registers conscious sensations such as touch, temperature, and pain and contains two major types of neurons essential for feeling and movement:

- Motor neurons – these allow people to take action depending on the stimuli the body receives. They carry information from the brain and spinal cord and the muscle fibres throughout the body.

- Sensory neurons – also known as afferent neurons, these carry information from nerves in the CNS and allow people to absorb sensory information before sending it back to the brain.

The somatic nervous system works opposite to the autonomic nervous system, which controls unconscious movement and sensation.

The Autonomic Nervous System

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) allows people to function without paying conscious attention and contributes to maintaining homeostasis within the body. This is the second branch of the PNS, responsible for involuntary bodily functions, including heartbeat, digestion, and breathing.

The ANS contains two branches that have complementary roles:

- The sympathetic nervous system – the sympathetic nervous system governs the body’s fight or flight response. In the face of a threat, this system prepares the body to respond by running, fighting, or potentially freezing. It triggers the release of hormones like adrenaline and noradrenaline, and controls bodily responses such as an elevated heart rate, dilated pupils, and increased breathing.

- The parasympathetic nervous system – this part of the ANS is also known as the ‘rest and digest’ system. It helps the body maintain normal functions and conserve resources. After a threat has passed, activating the parasympathetic nervous system slows the heart rate and breathing, reduces blood flow to muscles, and returns the body to a resting state.

The Enteric Nervous System

Another branch of the ANS that is often overlooked is the enteric nervous system (ENS). Also referred to as the second brain, it controls the function of the gastrointestinal tract and can operate independently of the CNS. The two are still connected and communicate via the vagus nerve, the longest nerve in the body.

The ENS coordinates with the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems to regulate gut function. When the sympathetic nervous system is activated and the body shifts into fight, flight, or freeze, the ENS redirects resources from the gut to the muscles to prepare for action. Conversely, when the parasympathetic nervous system returns the body to a state of rest, these resources are returned to the gut to promote digestion.

As well as controlling gut function and digestion, the ENS produces and responds to neurotransmitters similarly to the brain. It contains 100 million neurons and influences emotions and mental and physical health.[2] 95% of serotonin, a ‘happy’ hormone, is produced in the gut, and low levels may contribute to mental health conditions such as depression. Many people experience an upset stomach when distressed or anxious – another contribution of the ENS to mental health.

Trauma and the Nervous System

Traumatic events have a hugely significant impact on the nervous system. It affects every part, from the brain in the CNS to the ENS. For example, many people experience physical aches and pains after a traumatic event, even if it is not physical in nature. The nervous system influences this; in the case of stomach aches, the ENS has been affected and is dysregulated.

Trauma also shifts the balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems. Instead of activating the parasympathetic system to ‘rest and digest’ after a traumatic incident, the body can remain stuck in fight, flight, or freeze. This can contribute to hypervigilance, anxiety, and sleep problems.

When the nervous system cannot regulate itself, it can have severe long-term consequences. In part two of this series, we will examine how trauma impacts the nervous system, including how the fight, flight and freeze response can affect the body and how it connects to Polyvagal Theory.

If you have a client or know of someone struggling with anything you have read in this blog, reach out to us at Khiron Clinics. We believe that we can improve therapeutic outcomes and avoid misdiagnosis by providing an effective residential program and outpatient therapies addressing underlying psychological trauma. Allow us to help you find the path to realistic, long-lasting recovery. For more information, call us today. UK: 020 3811 2575 (24 hours). USA: (866) 801 6184 (24 hours).

Sources:

[1] Thau L, Reddy V, Singh P. Anatomy, central nervous system. [Updated 2022 Oct 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing

[2] Hadhazy, A. (2010, February 12). Think twice: How the gut’s “Second brain” influences mood and well-being. Retrieved January 16, 2023, from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/gut-second-brain/